Description

The advent of the blowing tecnique, free or combined with the use of moulds, revolutionised the glass industry and allows a wide-scale spread of the glass objects due to the reduction of technical working time and the possibility to create a great variety of forms in a short time.

The invention of the blowing tube occurs in the Middle East: the oldest record comes is in Jerusalem in a context dated the first half of the 1st century AD. The first trade of blown glass coincides with the conquest of Egypt (31 BC) and the establishment of the principality of Augustus at the end of the 1st century (27 BC -14 AD): political and economic factors combined with the intensification of maritime trade in the Mediterranean and the refinement of technical knowledge, aid the wide-scale spread of these objects in the Romanised world, up to the their predominance on the markets during the 1st century AD.

The conquering of Hllenistic reigns determined an influx of wealth and specialised craftsmen from the eastern Mediterranean: workers and workshops were established in Rome, Campania (Cuma, Pozzuoli) and along the high-Adriatic coasts (Aquileia), areas which had maintained commercial relations with Greece and the eastern Mediterranean for a long time.

A vicus vetrarius existed near Porta Capena in Rome, important production centres spread eastwards and westwards in the Mediterranean (Avenches in Switzerland, Lyon and Saintes in France), often characterised by a common formal-sylistic language.

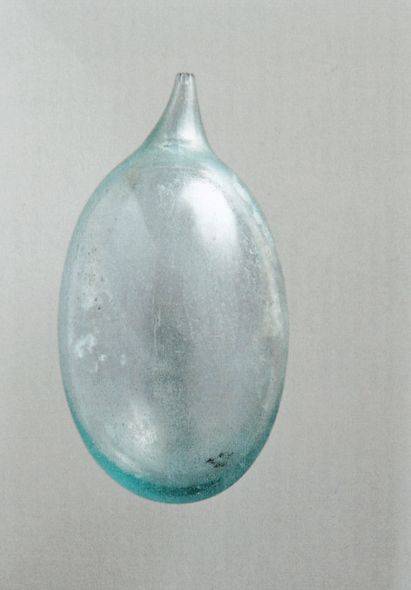

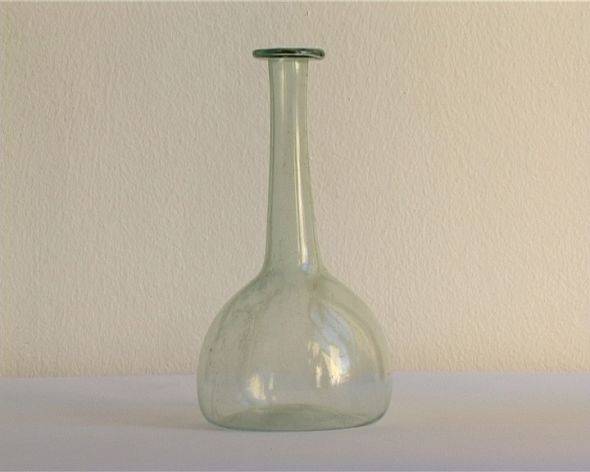

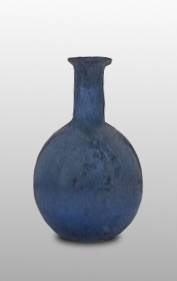

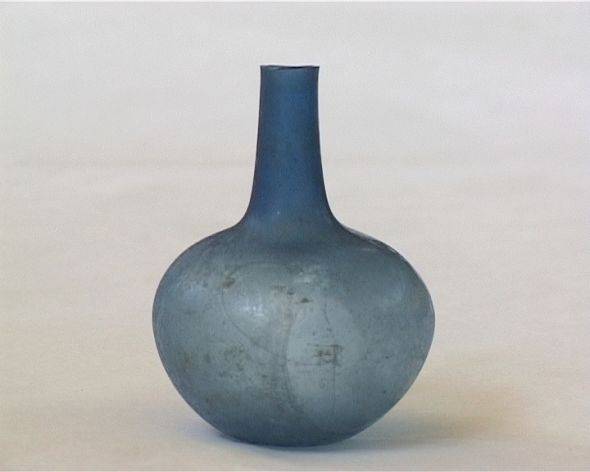

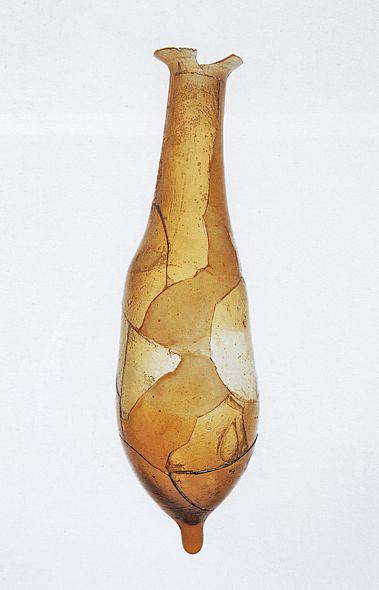

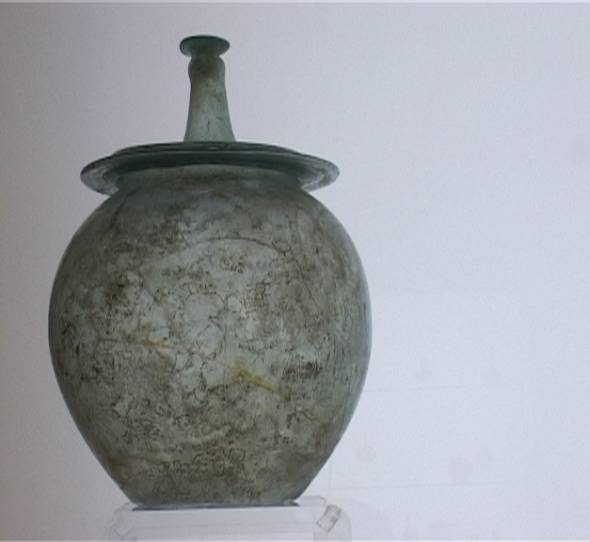

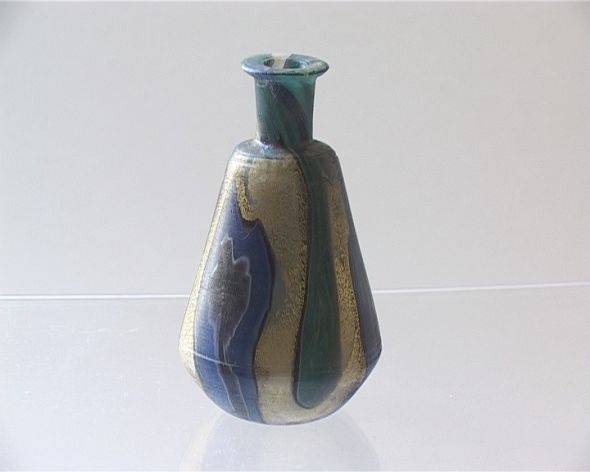

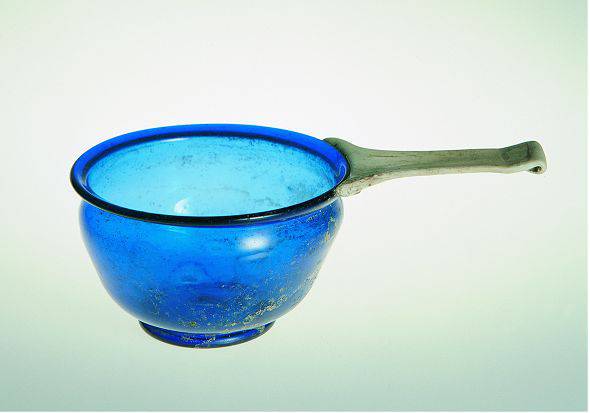

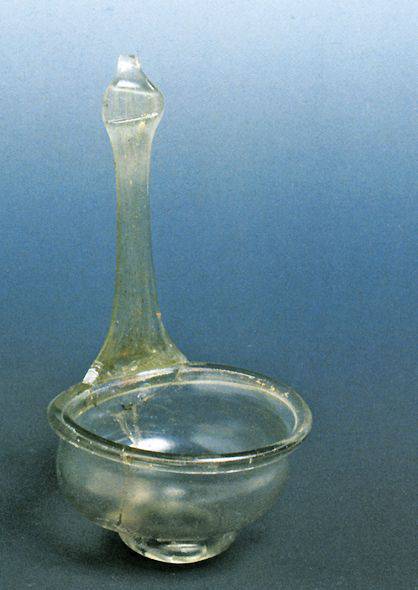

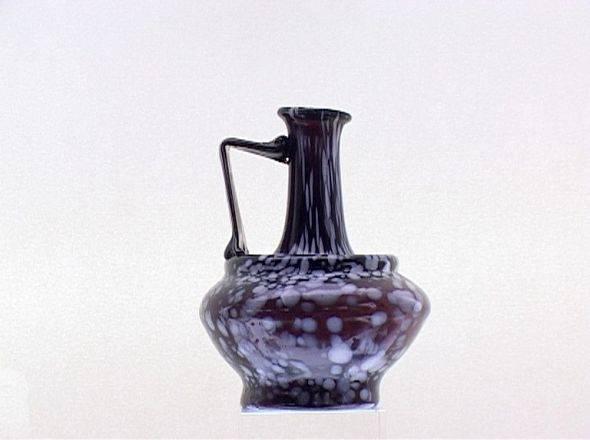

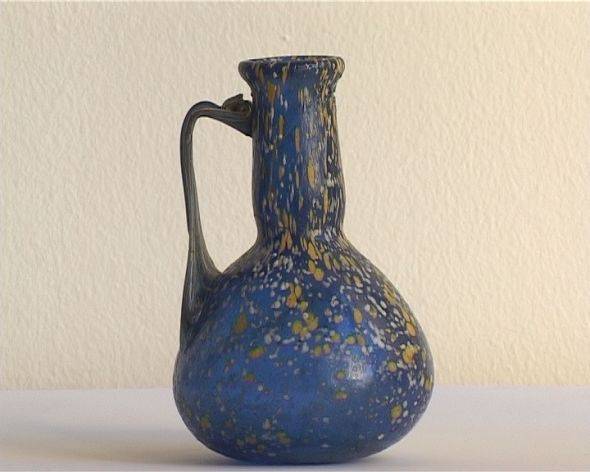

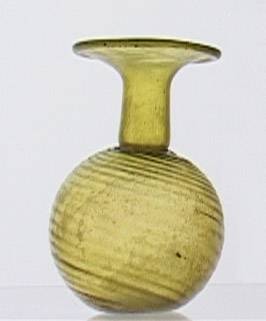

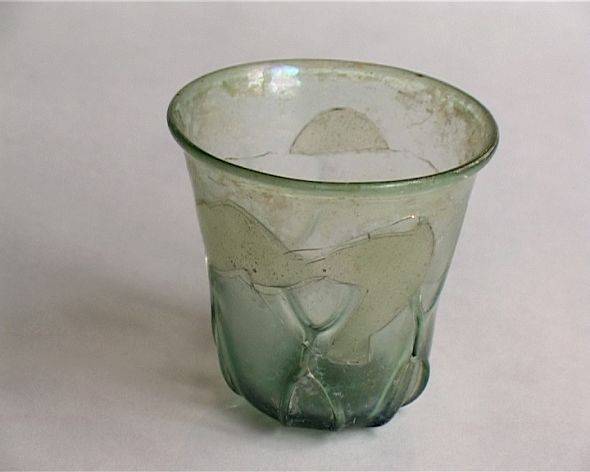

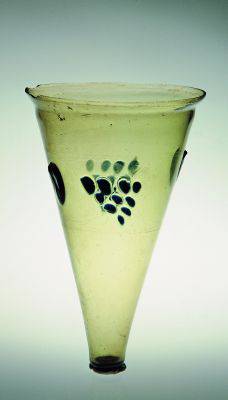

From a product reserved for the social elite, glass becomes an everyday item for all social classes alongside ceramic and metallic dishes which are often the inspiration for the forms. In the initial phase of production, blown coloured glass is frequently used, obtained by the addition of metallic oxides (photo 1); from about the middle of the 1st century, the use of natural glass of a blue colour prevails (photo 2), while towards the end of the 1st century AD, uncoloured, thin and transparent glass is again preferred (photo 3).

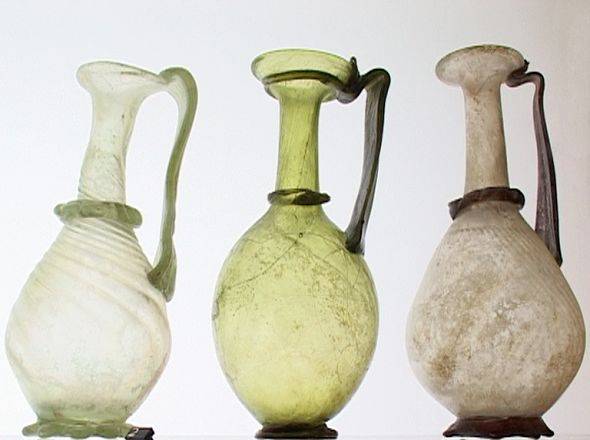

A particular field of application of the new blowing technique is the class of containers for ointments and perfumed balms, the ampullae vitreae, which had very wide-scale spread both in the eastern and western provinces of the empire during the 1st century AD (photos 4-5), and they brought about the rapid disappearance of Hellenistic ointment-holders on friable core.

The initial phase of production had taken place in Syria-Palestine in a period from 50 and 25 BC, spreading at the end of the century in southern Italy too (Campania coast). In the Augustus-Tiberius era, small pyro-form balm-holders, globular and disc-shaped, in strong blue, yellow and violet colours, are produced in the north of the peninsula in the workshops in Aquileia (photos 6-7-8).

In the Canton Ticino and the areas west of Verbano, particular ointment containers in the form of a dove and with a spherical body in multicoloured glass were produced at the same time (photos 9-10).

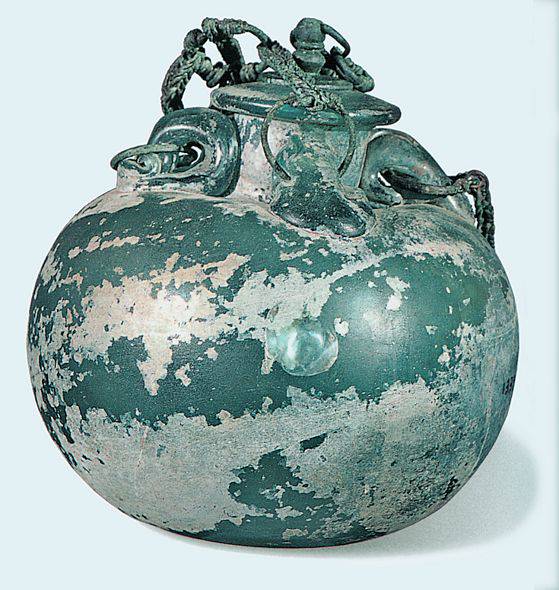

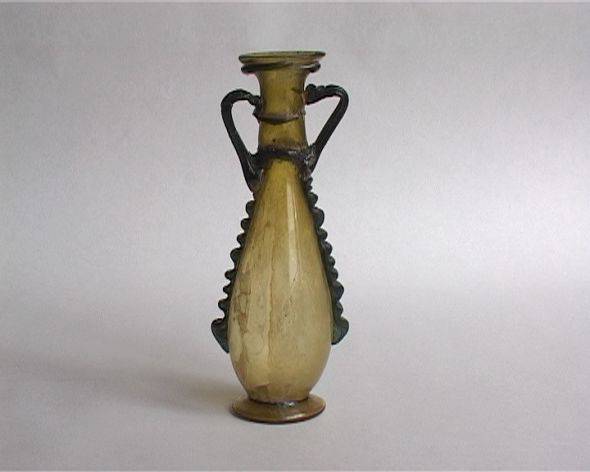

The small miniature tapered down amphoras (photos 11-12) resembled the formal clay-pot repertoire and were frequently discovered in Pompeii and in northern Italian workshops; the oil jars for the palestra, the aryballos, equipped with a chain for hanging, also resembled them and were connected with thermal bath use (photo 13).

Successively, during the 1st century, the industrialised production of balm holders which are tube-shaped or with a conical-trunk body with a long neck to slow down the evaporation of the content, sometimes even bi ones, appear and are characterised by the schematic repetitiveness of the forms and chromatic uniformity of blue glass.

The group of containers used for women's cosmetics also includes boxes, vase-formed balm-holders and bag-shaped cups made with common glass, with coloured glass sticks used to mix the ointments and makeup products.

For kitchen and tableware needs, glass containers of various styles and dimensions were available on the market: bottles, vases, plates, cups and glasses, which were favourably received for their functionality and impermeability.

The western production in common glass, generally blue, includes parallelepiped-bodied (photo 14) and ovoid vases, of various capacity, with or withour lids (photos 15-16), characterised by plastic handles: these were used for keeping food.

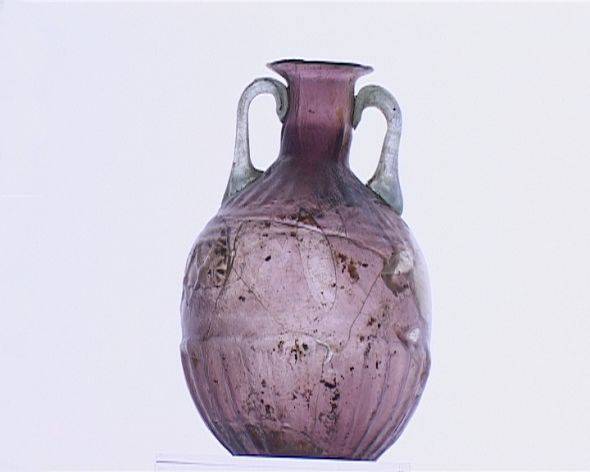

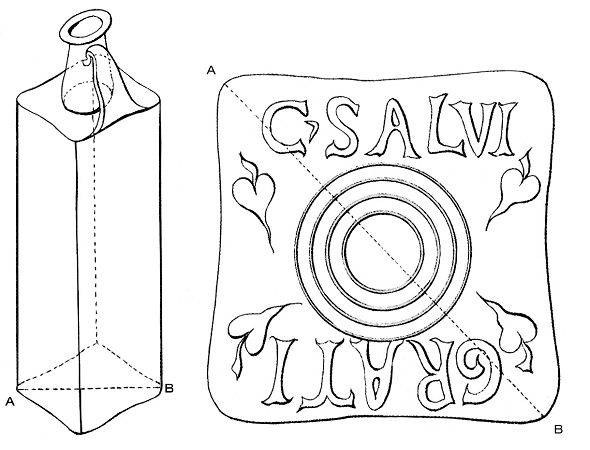

Rare wines (Marziale, Epigr. II, 40) could be kept in glass amphoras made in Campania (photo 17) or like the garum in a rare type of container, a amphoriskos with pouring spout (photo 18), but the most frequently used containers in the kitchen and tableware were conical, cylindrical and prismatic bottles (photos 19-21). Those with a cubic and parallelepiped body were favoured for transport due to the ease of stocking: they appear in western productions mainly in the Padana and north eastern areas of Italy, but are also frequent in the East (photo 20).

Tableware was inspired by contemporary ceramic dinner services: the apodal shape of plates, similar to sealed pateras, occur frequently in the first century, made with common blue and green glass. They come with acetabula, small containers for sauces, of an hemispherical form and in various shapes (photos 22-23).

The most frequent type of glass during the 1st century AD has a lengthened ovoid body, disc foot and stays this way for a long time with slight variations (photo 24).

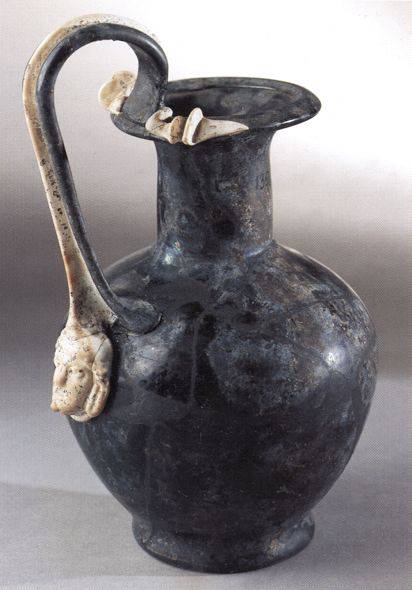

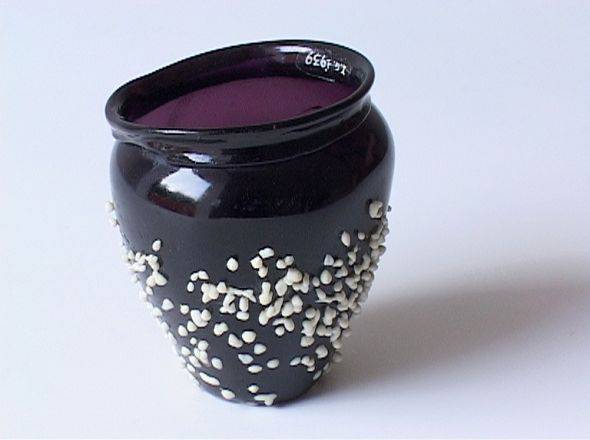

In the uniform panorama of every-day use dishes, more refined services were also produced, due to the type of glass used, like completely opacified coloured glass or obsianum glass which looks like obsidian (photo 25) which is mentioned by Pliny (Nat. Hist. XXXVI, 196).

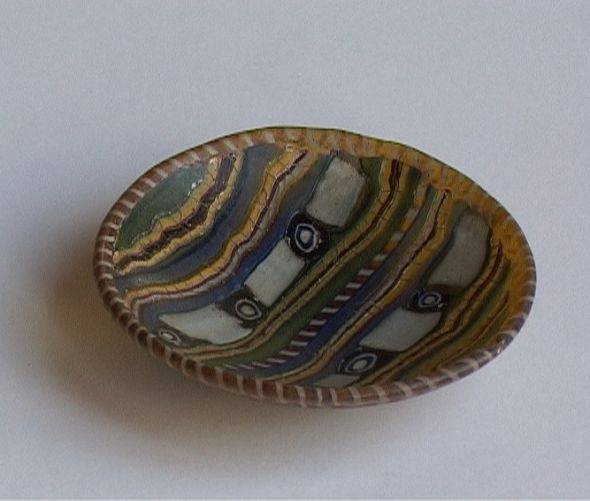

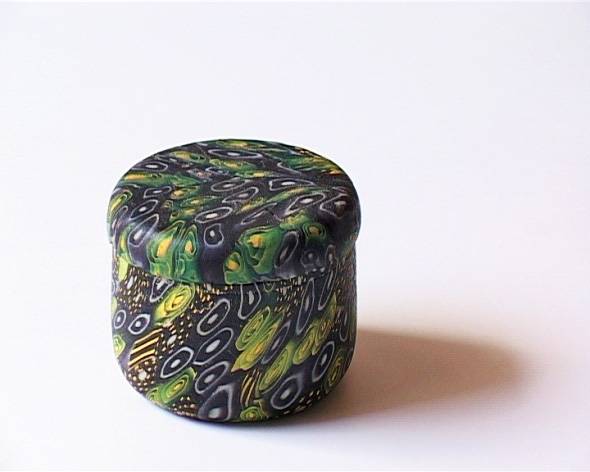

Even after the advent of blown glass, the old method of coating over a mould and core-forming still continued to be used over the course of the 1st century AD. Under the guidance of the Hellenistic tradition, in central-southern Italy, which had adopted the ideas from the eastern area quickly and with new forms, what becomes established are working with monochrome and polychrome glass (mosaic, bands (photos 27-28-29), marbled reticella (photo 26) , 'millefiori' (photos 30-31) and the more refined production using gold bands with examples of pissidi and luxury ointment-holders (photos 32-33).

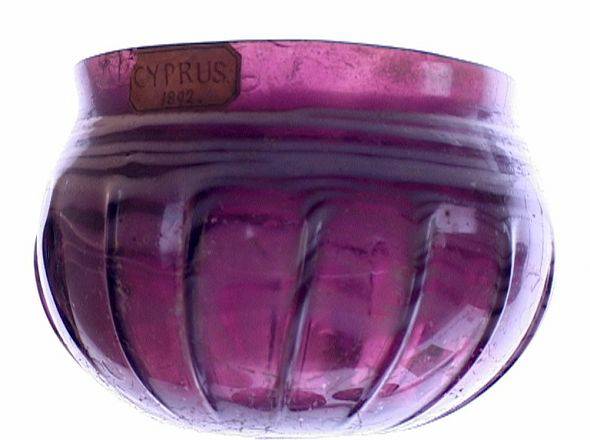

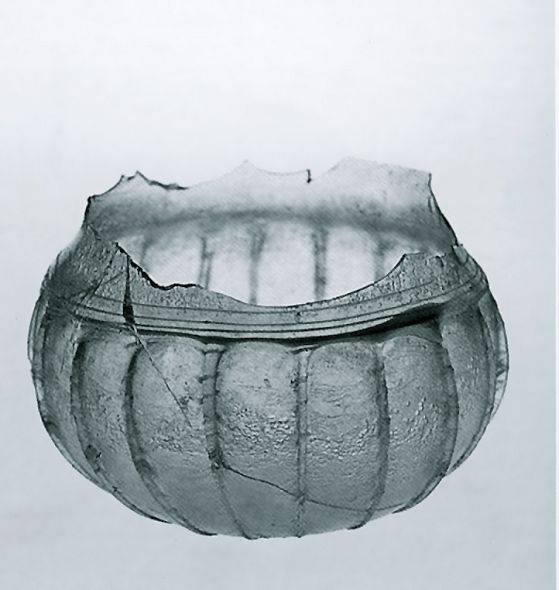

Ribbed cups are produced in monochrome (photo 34) coloured and mosaic glass are produced above all in the western regions of the empre in the first half of the 1st century, while the version in green-blue common glass, produced in various workshops in northern Italy, continues for a good part of the 1st and 2nd centuries with important discoveries in all the settled areas. These important productions are frequently found in the cisalpine area of Italy, where where they were widely exported towards the transalpine provinces (Locarno, Vindonissa, Treviri).

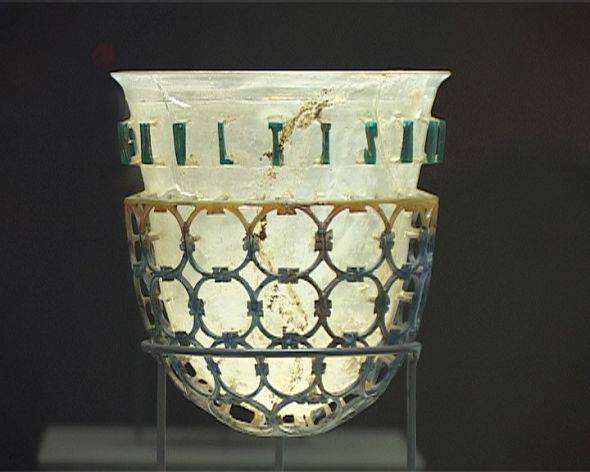

In the eastern context too, the production of refined coated core-formed objects in the furrows of tradition, continue to be produced in the first half of the 1st century AD, in particular elegant monochrome drinking vases, carved, finished on the wheel, that look like metallic models (photo 35).

This technique continues to be used to produce ornamental gems (photo 37) in molten glass and for many other small objects, like pearls and movement pieces for games (latruncola) (photos 36-38).

Around the middle of the century, the Roman-Italic production of coated polychrome vases is almost completely exhausted, as it requires a significant production effort.

In the eastern Mediterranean area and, in particular, in Syria-Palestine, the new moulded-blowing technique was spreading, which facilitated the execution of complex forms with relief decorations. In the initial phase of application of the new technology, in the second quarter of the 1st century AD, we can place the activities of the sionio Ennione, a rare case of vitrarius which who signs his work, mainly refined two-handled cups, jugs, boxes in transparent monochrome glass, decorated with dots and phytomorph relief motifs, found in Greece, Israel and prevalently in the West, in particular in northern Italy.

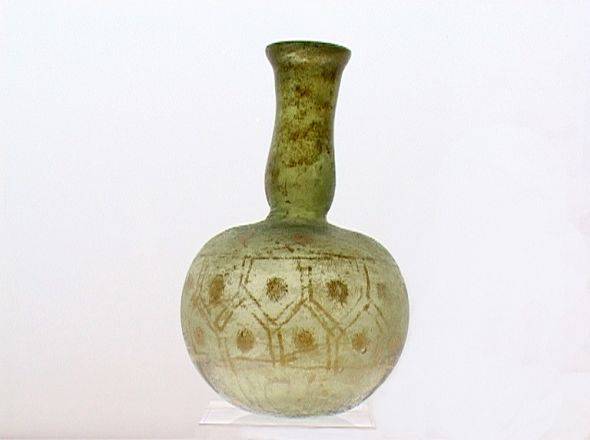

Miniscule containers, cups, small bottles and especially dotted ointment-holders with complex relief plant motifs which also appear on the so-called 'Sidonian flasks' and on later traditional objects, can be attributed to him, and they reach the Padana plains and the western provinces.

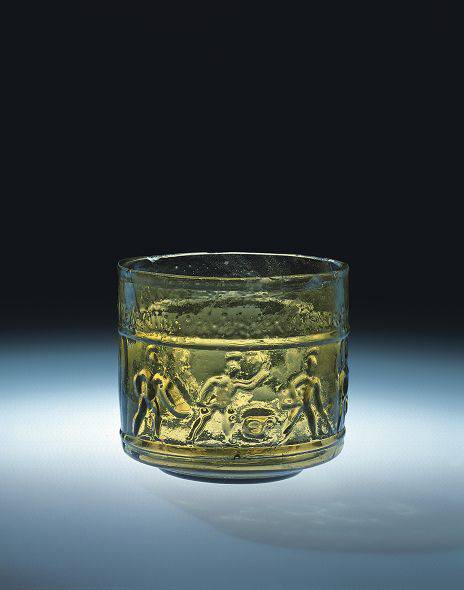

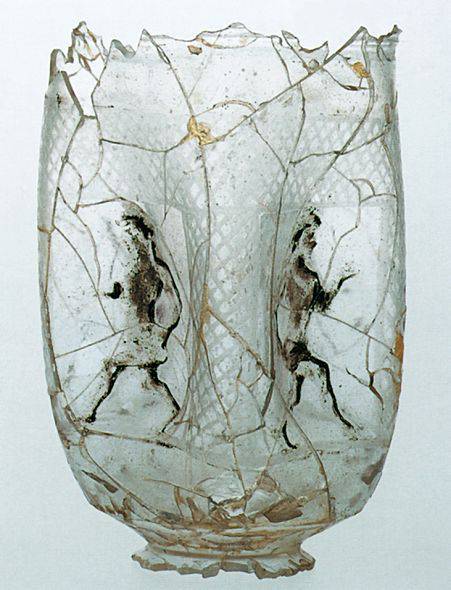

In addition to the great Ennione, the eastern context is characterised by the presence of multiple glass schools of notable technical expertise (Aristeas, Artas, Jason) which spread mould-formed decorated products with phytomorph motifs in the west. Particular series of cups and glasses with an augural-celebrative significance, with gladiator and circus scenes, are linked to this production.

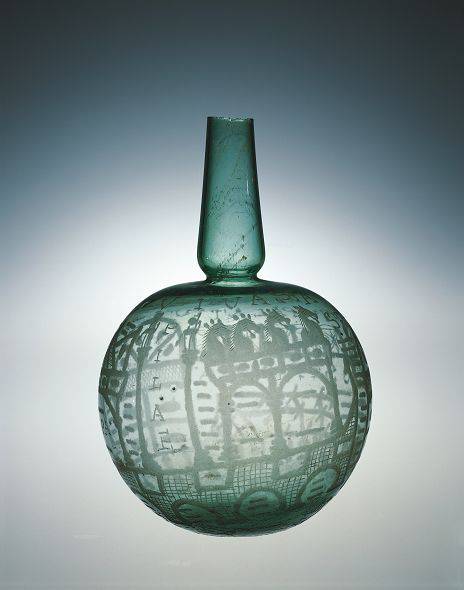

With the consolidation of the production activity, he models produced in the eastern Mediterranean were reproduced in the western workshops, with innovative formal and decorative creations; amongst the objects blow-moulded, during the 1st century, what stands out are the transparent glasses with 'lotus buds', 'node'-style, which call to mind the legend of Hercules or with geometrical-floral decorative composite motifs or with pictures of mythological figures within Templar structures.

The same technique was used to produce containers with geometrical decorations and bottles with helicoidal ribbing.

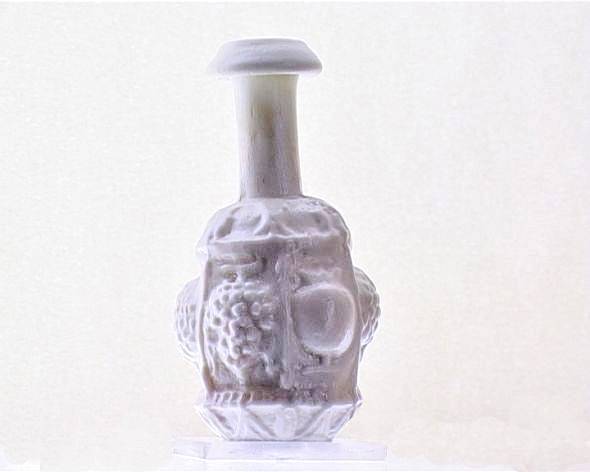

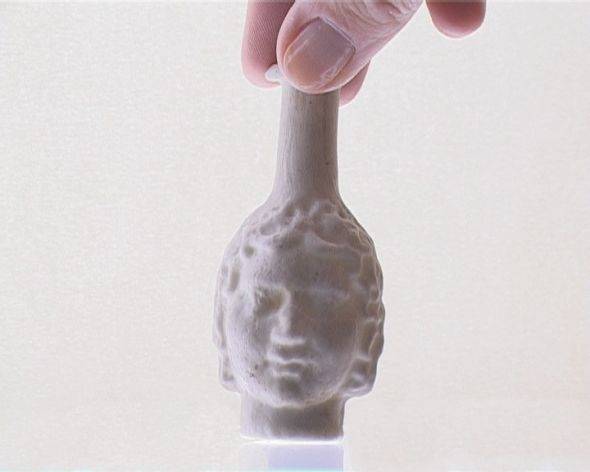

The plastic full relief forms of bunches of grapes, dates, pinecones and human heads, used for ointment-holders, are produced in the east, but seem to be equally spread in the west during the 1st and 2nd centuries.

The blow-moulding technique which was initially reserved for important precious objects, is transformed into series production to make cubic-bodied, prismatic and cylindrical bottles, both in the East and in Italy, in particular in Aquileia, as supported by the mark of Sentia Secunda which produced Aquileiae vitra, found in Linz.

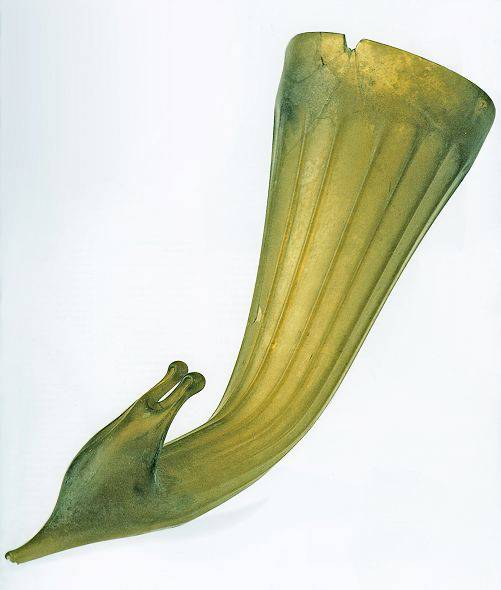

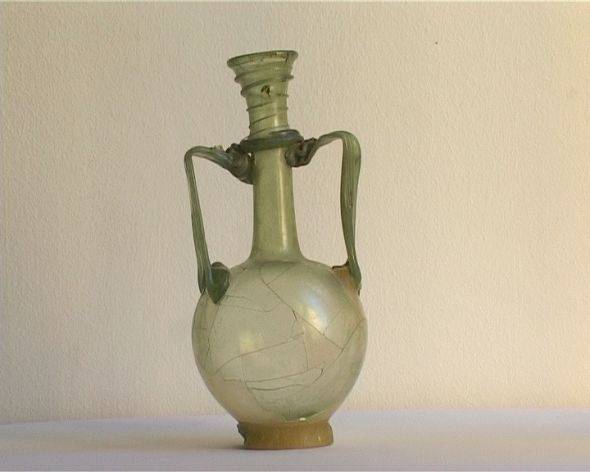

At the same time, alongside examples of high craftsman effort, refined blown glass was produced with a toreutics inspiration. In the production of dishes for functional kitchen use for pouring and drinking, recourse was often made to the imitation of metallic forms of the late Hellenistic era: jugs with ovoidal bodies and wide necks in coloured glass, jugs with moulded handles in molten glass resembling elegant classical forms (skiphoi, kantharoi, askoi, modioli, gutti) or unusual forms of rhyta, simple drinking horns or zoomorphic endings, mainly for ritual use, produced by the different productions discovered in the western provinces, in the transalpine areas, in the Padana plain and the Vesuvian cities.

Plates and cups in uncoloured transparent glass with scalloped side handles, which is a motif inferable from silver dishes, can be attributed to the eastern production between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. The circulation of these products followed the Mediterranean routes and their production, taken up also in the West, perhaps following the activities of travelling vitrarii, also include northern Italy.

From the great quantity of glass produced for daily use, some objects using different technologies emerge, often of a notable artistic quality, embellished with various ornamental forms.

A particular taste for 'dot' and 'plumed' decoration seems to characterise, not-exclusively, the production of northern Italy and the Canton Ticino over the course of the 1st century. Polychrome and monochrome granulation decoration, tinges of colour and different types of threads that appear on small amphoras and jugs, on biconical bottles and vases, have been interpreted as the desire to imitate the more costly mosaic glass and hard stone veining.

The same taste seems to explain the production of 'zarte Rippenschalen', small-dotted cups with molten glass threads wrapped around in a spiral, concentrated in the eastern and western cisalpine area, in the Danube area and in the Reno Valley.

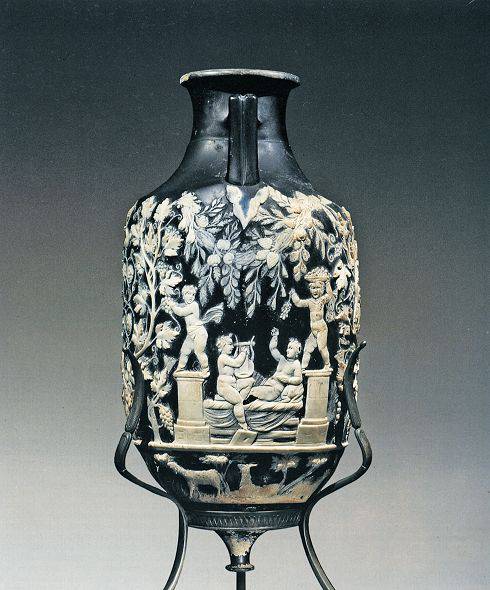

Cameo glass, perhaps the most esteemed ancient glass art product, was a type of glass with two or more over-lapping layers, generally blue and white, with a complex technique, inspired by the decorative Hellenestic repertoire with a Dionysian theme. The known specimens, of a high artistic level (jugs, cup amphoras, skiphoi, paterae, panes), prevalently of a Pompeian origin, dated from the first half of the 1st century, belong to a limited production, for clients of high standing, even Imperial, as in the case of the Portland vase and the amphora with the grape harvester cupids from Pompeii.

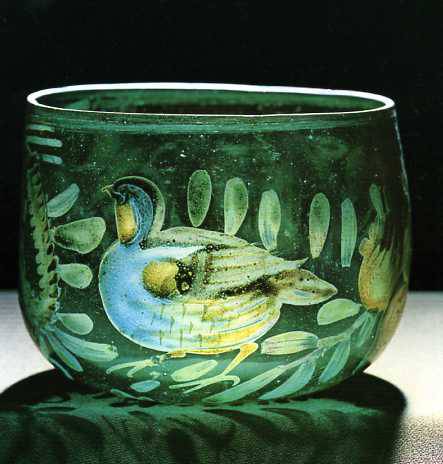

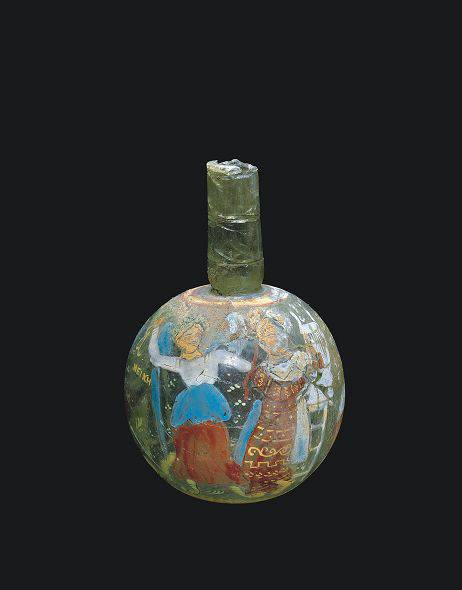

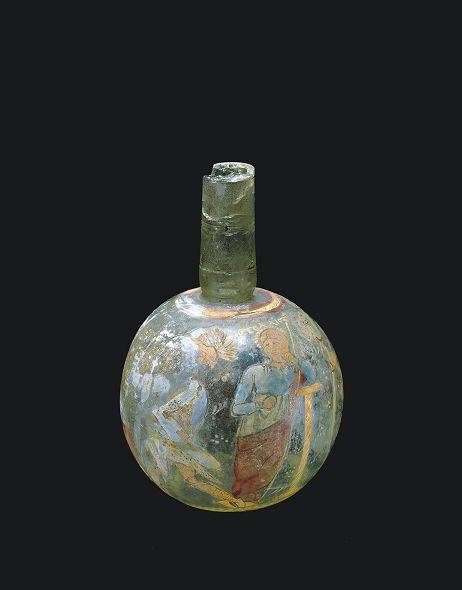

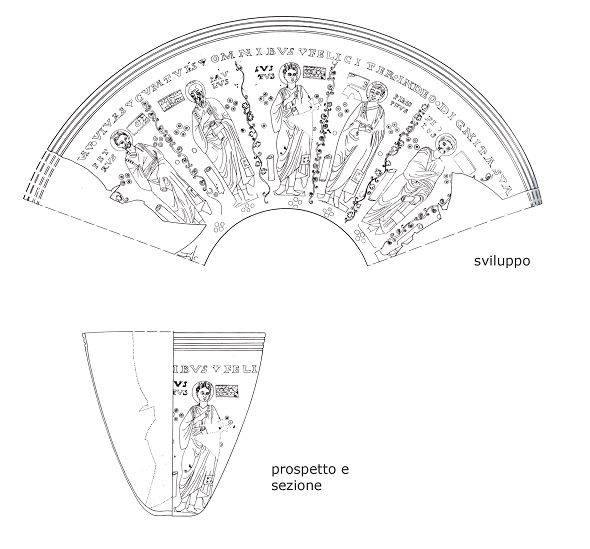

The production of painted glass can be traced back to the creativity of the eastern world. In this context, we can place objects of exceptional importance like the series of cups and amphoriskoi from the first half of the 1st century AD decorated with animal and plant motifs (birds on vine-shoots, ducks, gazelles, fish, pygmy battles) from Hellenistic tradition and of an Alexandrian taste, wide-spread both in the Mediterranean area (Egypt, Algeria, Greece) and in the Black Sea area and in central-northern Italy, in the Ticino and the transalpine provinces (Switzerland, France, Germany, England). The high number of discoveries in the West has led to the supposition of a probable production in northern Italy to supply the western market.

A vacuum glass from Aosta (Italy) at the end of the 1st century AD, of eastern production, probably Alexandrian, with pictures of a painted figure with Phrygian cap and loincloth, could be the morphological and stylistic antecendant of the later glases from Begram (Afghanistan). Painted objects with genre subjects or naturalistic widespread in the West, express, in the continuation of exchange relations, the predominance of precious objects of eastern origin, which circulated between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD.

From the middle of the 1st century AD, highly refined vases become wide-spread, in high relief glass made both by mould-forming and either free blowing or mould-blowing, decorated by plant motifs (lotus flowers, small roses, lance-shaped leaves), animal motifs (Cephalopoda shells) and geometrical motifs. This technique will last for a long time and will characterise precious products from the middle to late imperial age.

From the 1st century AD, glass is used more frequently in the architectural field too: window panes, obtained with the moulding method, were set up on wooden frames and used in public buildings, principally in thermal baths and private domus. The invention of blowing increased the use of flat glass for functional and decorative uses over the course of the 1st century.

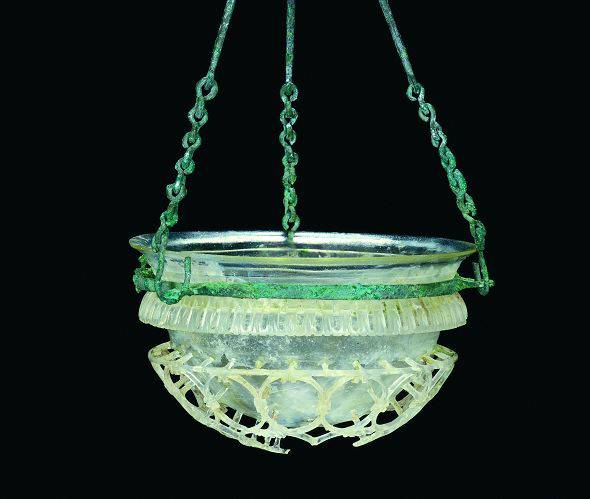

Oil lamps and lanterns, daily use objects, attest to the use of glass in the lighting field too.

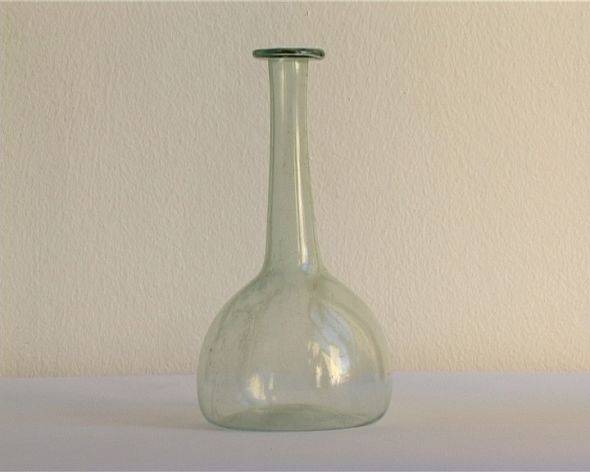

Towards the end of the 1st century, a new change in tastes came about which brought about a preference for glass which was uncoloured, thin and transparent. This preference affected the production of current glass, from unguentary vases to containers for domestic use, both in the East and the West.

During the 1st century and even more so in the successive one, the production of common conical-trunk bodied unguentary vases assumed a morphological characteristic. The body is flattened and the neck is lengthened, bottle ointment-holders undergo a wide-scale spread. In addition to bulb-shaped bodies ointment-holders and the candlestick type ones, there are unique models characterised by vacuum bodies or lentoid shaped ones of Gallo-Rhine production. Proof that the imperial house was controlling the production of balm and ointment-holders, are the moulded seals or mint marks taken from coins that appear on the bottom of some types of containers.

Between the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, one or two-sided cephaloform ointment-holders depicting Dionysus or Medusa are produced; 3rd century phials are still mould-blown with schematic geometrical decorations.

Unguentaries often held pharmaceutical compounds: the so-called 'mercurial' bottles, for specifically pharmacological use, were wide-spread in the west and in particular in the Gallo-Rhine area. The cubic bottles too were used to hold medicines, as the discovery context proves (Murecine in Pompeii).

The same exuberant decorative taste which characterised the western workshops, especially in the Rhine valley, is also seen I a typical production of the Syrian-Palestian glass work from the late-ancient period, like the multiple double bodied unguentaries decorated with inventive spiral or zig-zagged threads.

The craftsmen's creativity is also seen in the type of small containers for cosmetics or medicines, like the small bottles characterised by a variety of decorations and the small vases decorated with ontrasting coloured threads, applied in relief zig-zag.

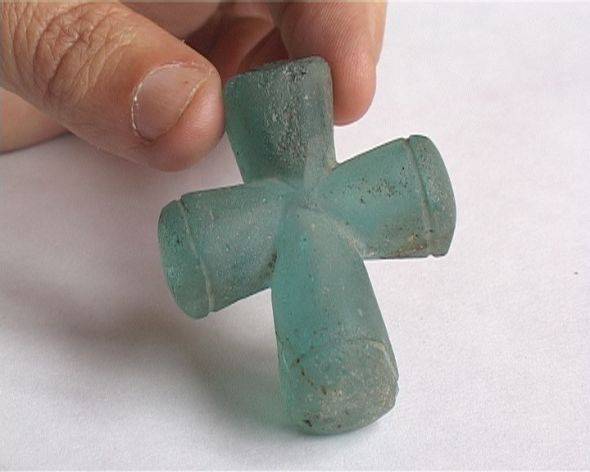

In the late ancient era, with the advent of the Christian religion, the last forms of unguentaries with lengthened core-formed body characterise the burial of the clergy or however should be connected to the new rite ceremonies. Due to their content or their origin, some objects, tied to the pilgrimage practice, become articles of devoutness.

From the 1st century AD, production activities from the Rhine province had arisen, which during the course of the 2nd century had developed independent creative characteristics and technical expertise. The creativity of Cologne had been applied to traditional forms of unguentaries and bottles, remoulding proportions and decorations.

Over the 3rd century, the spread of glass products reduces considerably due to the changed economic conditions and the changes in tastes. There is a restricted number of forms tied to pouring functions, especially bottles, flasks and glasses of simple features. Products from the Rhine glassworks of a more complex conception are forced onto the western and Padana markets, embellished with plastic motifs and threads, imitation objects.