Description

In the Hellenistic period, glass manufacturing undergoes a period of rebirth and flourishing development, coinciding with the widespread commercial renewal of luxury and consumption goods, following the changes deriving from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the consolidation of the powerful dynasties which define the new political and economic situation in the east Mediterranean. In Egypt, there is the establishment of the Ptolemaic dynasty, in Syria and in Mesopotamia the Seleucids, in Greece and Macedonia the Antigonidi.

Even after the fall of the Persian empire in 3330 BC, the achemenide artisan products continued to be imitated in the Greek and Macedonian workshops.

Glass production centres rapidly multiplied: alongside the Syrian-Palestinian coastal area, in Sidon in particular, Alexandria founded in 332 BC becomes one of the principal production centres of Hellenistic glass.

In the cultural koiné of a Greek background, the initial phase of Hellenistic glass production yet again provides the basis for the previous era's tradition (photo 1).

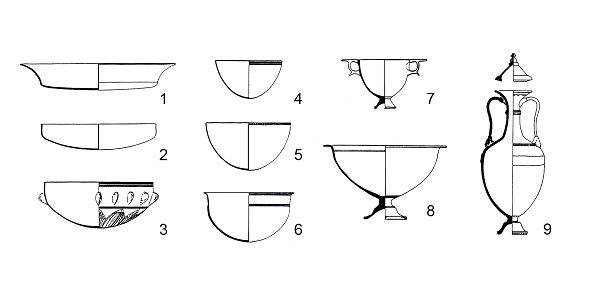

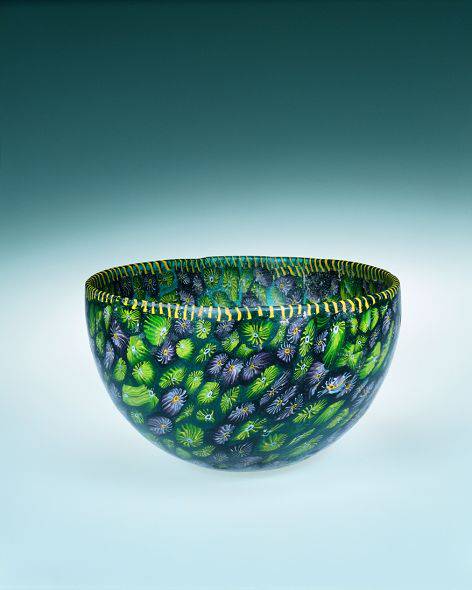

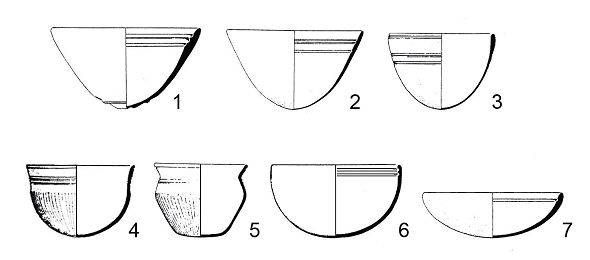

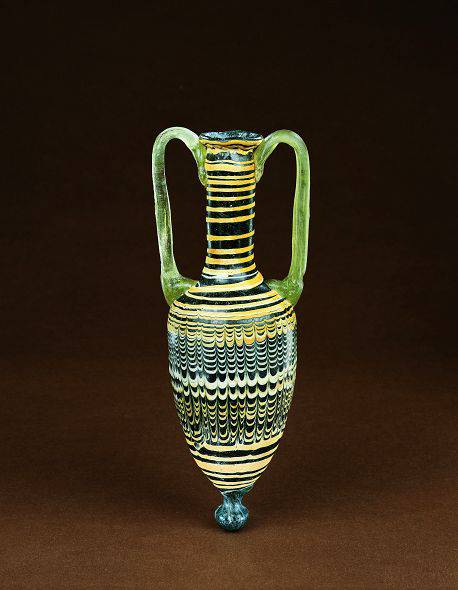

During the 3rd century BC, carved decorations of a phytomorph type are recurrent on the bottom of dishes in transparent glass, yellowish and greenish, mainly elegant cups for drinking. It is only at the end of the 3rd-2nd century BC, most probably in the Alexandria workshops, that new stylistic trends emerge following technological innovations and the rediscovery of mosaic glass: the characterisation of the typically Hellenistic production of mould-formed glass is exemplified by the exceptional grave discoveries in Canosa di Puglia, the so-called 'Canosa Group' (Tab. 1).

New glass working methods, like mould-sagging, aid the production of toreutics-inspired dishes, mainly of an open shape and of large dimensions, morpholoigically varies: big plates, trays, skiphoi, kadoi (amphora) and cups on foot (crater) (photo 2) were associated with hemispherical or conical-shaped cups, rare specimens of high excellence.

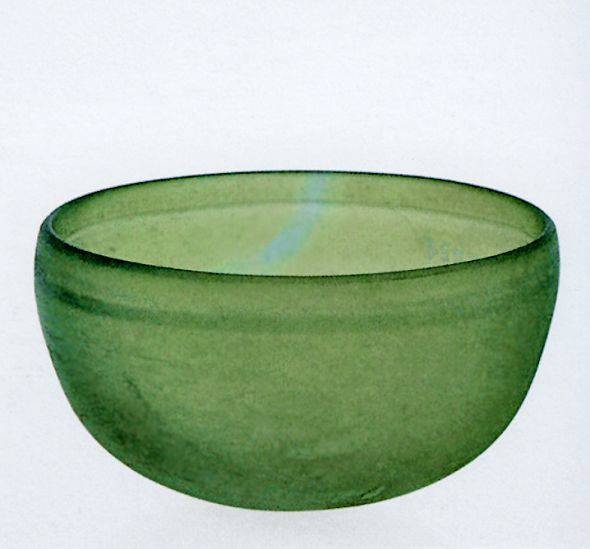

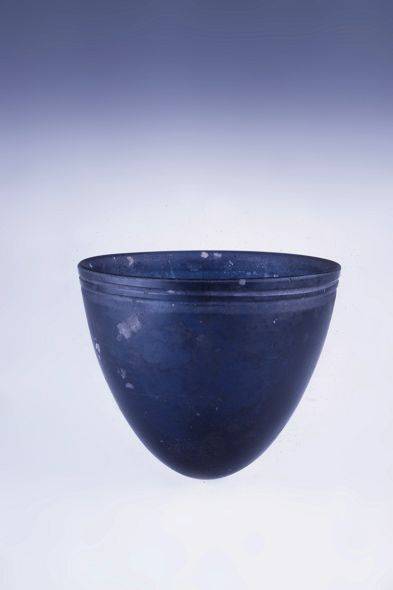

We are dealing more frequently with shapes in coloured monochrome glass, often translucent or almost uncoloured (photo 3), simple profile, polished style and with simple horizontal groove decorations and, in some cases, with dishes in polychrome glass 'mosaic style' in the 'reticella version' (photo 4) or star motifs (photo 5) and spirals alternating with coloured glass wedges (photo 6).

Particolar mention should be made of the refines cups from the end of the 3rd-2nd century BC, made in the gold-glass technique, with gold-leaf plant motifs, probably produced in Alexandra (photo 7), which look like precious metal prototypes.

The spread of Hellenistic glass products, rare and costly, of exceptional technical and formal quality, reaches the Mediterranean, Asia Minor, Cyrenaica, Greece and the Italian coasts via trade routes.

From the 3rd-2nd century BC, polychrome and monochrome dishes set foot on the southern Italian market, intended for a small Italiot élite.

Oriental products of a sumptuary character are found in Sicily both in funeral and house contexts between the end of the III and the beginning of the 2nd century BC, like the white glass cup of Syrian production in Naxos (photo 8), with a slightly oval profile, the deep cups and the fragmentary plates in uncoloured glass from Morgantina, attributed to craftsmen in Alexandria.

Contemporary imports of oriental glass are also found in southern Italy (Magna Graecia). The necropolis tomb in Canosa, the ancient Canusium in the Daunia, have given us a considerable group of specimens of high technical and stylistic quality: sandwich gold-glass cups with gold-leaf flower motifs, elegant skyphoi and lobed cups with plant decorations carved on the base in uncoloured glass (photo 10), big plates made both in glass-mosaic and colourless with painted and gilded decoration, polychrome or reticella cups alongside simple hemispherical cups in coloured monochrome glass.

The continuation of trade over the course of the 3rd century BC with the Middle Eastern area and the stability of the trade circuits, explain the presence of refined examples of a production for the elite along the centre-north part of the Adriatic coast.

In the context we have the polychrome reticella cups (photo 11), mosaic ones with spiral-form motifs (photos 12-13) and the big plates in transparent glass with traces of painting and gilding from the second half of the 2nd century BC from Ancona, in the Piceno area. In the same cultural context, there is a version of a green monochrome cup which comes from Adria (photo 14).

Over the course of the 2nd-1st centuries BC, maritime trade also reaches the Tyrrhenian coasts: from Etruria come cups and composite mosaics and vases in polychrome marbled glass that looks like hard.

Similar associations of Hellenistic dishes of exceptional refinement, belonging to the 'Canosa Group', are found along the coasts of Southern Russia (Olbia, Kerch), an important area for the supply of wheat for the Mediterranean market, in particular the Hellenic one.

At the end of the 2nd and during the 1st century BC, the glass industry reaches its manufacturing peak. At the same time, the production of monochrome glass in the Syrian-Palestine and Egyptian workshops notably increases and is spread in all the regions facing the Mediterranean, as the discovery in Delo and Tell Anafa (Israel) support. What we are dealing with are mainly hemispherical or conical shaped cups with smooth walls or fine horizontal line-cuts, often in coloured glass (Tab. II - photo 15), with close resemblance to clay pots - like the Megarian cup - or metallic objects, as supported by the remains in Anticythera.

Towards the end of the 2nd century BC the ribbed cup also appears, in molten mould-formed glass, natural or coloured (photo 16), which rapidly spreads in the Mediterranean are and the western provinces.

The production of original jars with lids (boxes), mould-formed in translucent reticella glass, can also be attributed to this period: a considerable number were found in Crete and were probably produced locally.

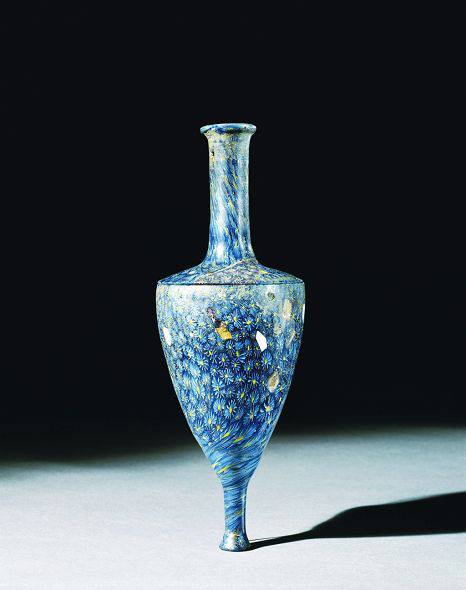

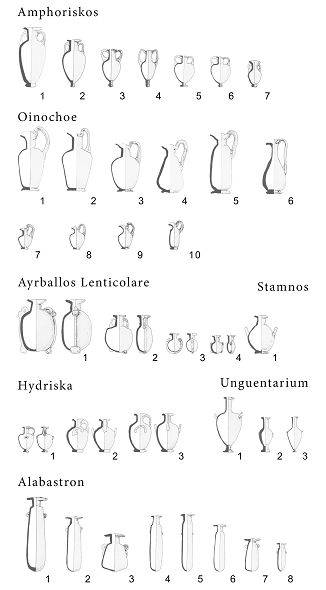

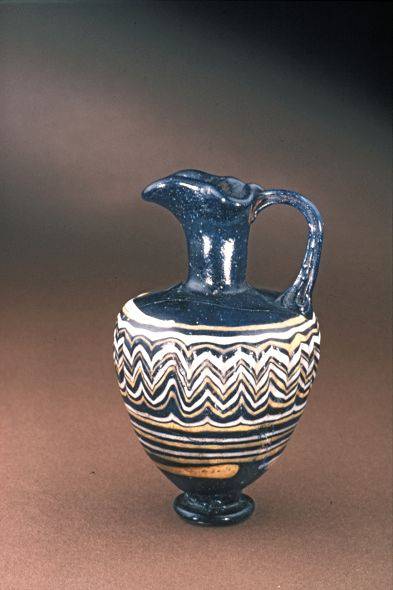

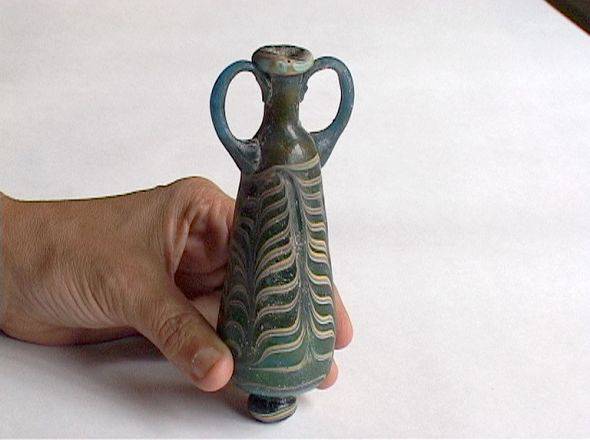

From the middle of the 4th century BC, production begins again also of containers for ointments and cosmetics classified in the so-called Mediterranean Group 2, which includes a new repertoire of miniature forms, like the stamnos and the hydria (tab. III, photo 17), and the introduction of new decorative models using feathered, scalloped, and zig-zagged bands (photos 18-19-20).

The distribution of these containers reaches the eastern Mediterranean: concentrations of notable importance localizable in the Celtic necropolises in the north (photos 21-22-23) and central Italy, in Magna Graecia, in Tessaglia, in Macedonia, in Bulgaria and in the Soviet Union, have led us to presume the presence of more production centres distributed in the western Mediterranean area.

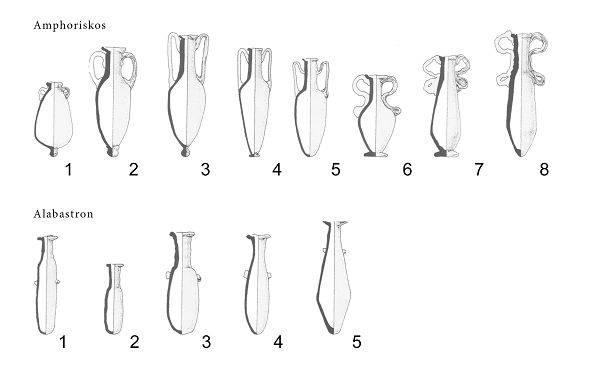

After a stagnation period, from the middle of the 2nd cent. BC, a new type of ointment-carrying container appears (alabastra, amphoriskoi) which can be classified to the 'Mediterranean Group 3' which includes a notable change in the form and size of the handles and resemble the production of ceramics and amphoras (Tab. IV) for carrying from late Hellenism.

The shades of colour and the decorative motifs are similar to those of the previous group; what is innovative is the production of handles and bases in clear translucent glass, different from the colour of the body (photos 24-25).

The high concentration of specimens in the Levantine regions generally, and particularly in the Syrian-Palestine one, has allowed us to hypothesise that the production centres can be localized in that area (photos 26), characterised by important production of molten glass cups, mainly uncoloured or of a clear-translucent colour.

During the 1st cent. BC, the innovative alabastra also appear, with gold bands (photos 27-28) with holed lids to be used as sprayers, widespread in the Eastern Mediterranean and in Italy.

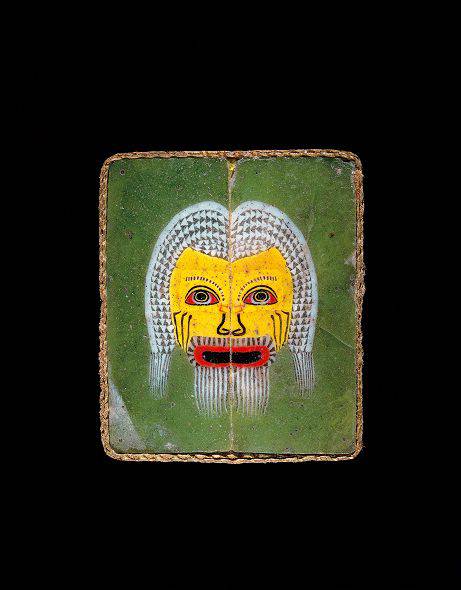

The production of ornamental objects also continues, like the formed vitreous pendants (photo 29): Carthage seems to have played a predominant role and the Phoenician contribution is fundamental. The production of typical products like the glass mosaic tessera (photo 30), the small plates with floral motifs and specialised finishing of pearls (photo 31) and bracelets both in the Orient and the West (Rhodes, Meare in Great Britain, Nimrud in Iraq and Manching in Germany).

Up to the 1st century BC, the production of glass objects remains substantially limited to the area of the Middle East: a real technological innovation in the working of glass will occur, only around the middle of the 1st century BC in Syria-Palestine, with the introduction of blowing, a system which will allow the wide-scale spread of glass objects due to the rapidity of execution.