Description

In the 9th century BC, there is a recovery in the production of glass objects. The location of this recovery is the Near East area.

The first discoveries come from Persia; other discoveries dated 9th-8th BC are in Phoenicia and Syria, where small plates and ivory panels carved and inlaid with molten glass were found, used as furnishing ornaments.

In Egypt, there seems to have been a stagnation up to the Hellenistic era, when the famous Alexandria craftsman centre was born.

Large scale production of vases start again during the 8th century BC; initial production seems to have been concentrated in the Mesopotamia and Syria-Palestine areas.

Findings of material during this period is also accompanied by the discovery of literary sources: in archaeological sites in Assiria, Anatolia, Babylon and particularly in Ninive (in the Assurbanipal library - 7th century BC), tablets were found, drawn up in wedge-shaped characters, which deal with the preparation of various materials, including glass.

The texts on glass are of enormous importance because they demonstrate that knowledge on glass art was not entirely forgotten during the dark age.

One of the first types of vases which must have been reintroduced during the recovery was that of monochrome vases melted probably using the lost wax technique, with very thick walls and almost transparent, often green in colour, whose shapes look like metal and stone vases.

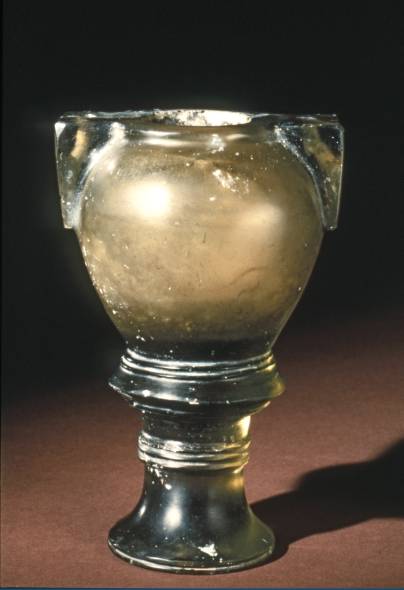

The cups, dated between the 8th and 7th centuries BC, were found above all in Assiria (photo 1); they are quite rare out of Asia, but two specimens should be remembered, one found in Crete and the Other in Italy, in the grave of Bernardini of Palestrina.

Closed-shaped molten vases are less common; the most famous is the so-called Sargon Vase, a cylindrical ointment-holder tapered at the top (alàbastron) found in Nimrud, with the name Sargon and two lions carved on the back.

Other specimens (alabastra, jugs) were found, in addition to Assiria, in Cyprus, Italy

(photo 2) and in Spain.

The origin of these cups and closed vases has not been determined with certainty, because there are few specimens left and are distributed widely from a geographical perspective. One of the areas of origin could have been Assiria, but some scholars have hypothesised a Phoenician origin too.

In the 8th-7th centuries BC, there was a regaining of production of inlays and mosaic small plates, albeit on a small scale.

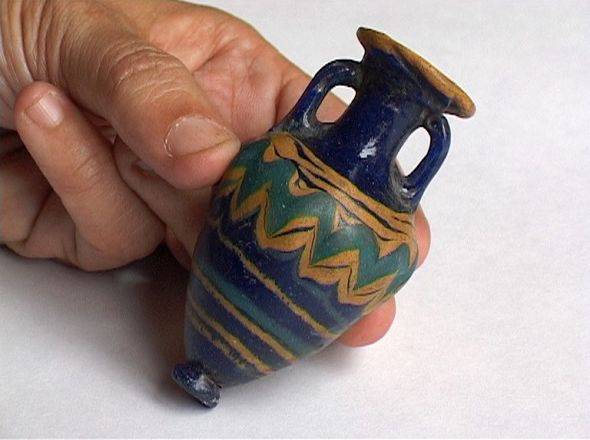

During the second half of the VIII century, molten vases reappeared again in Mesopotamia on a friable core. The prevalent shape is the alabastron, decorated with scalloped or ziz-zag lines.

The production, dated between the 8th and 7th centuries, is called 'Mesopotamic' on the basis of principle places where they came from, even if some specimens were found in the eastern and central Mediterranean.

Starting from the 7th century BC, core-formed vase production undergoes a new popularity thanks to the spread in the Mediterranean of these Mesopotamic products and thanks to the settlement on the island of Rhodes of producers and craftsmen from the Near East. Scholars have hypothesised that this industry influenced successive production of 'Mediterranean' jars.

Other alabastra from 7th century BC, which are thinner and with decorations placed differently (photo 3), lead us to believe that in this century other industries were developed, but their wide diffusion makes it difficult to determine the region in they were produced, even if in all probability the production occurred in the eastern Mediterranean.

Another class produced between the VI and IV centuries was that of tubes for kohl (photo 4), containers for black powder for eye makeup. These tubes, shaped on rods, must have been produced, depending on the type, in the eastern Mediterranean, Iraq and Iran.

In the 7th century BC, following the destruction of the Assiro reign in 612, the production of mosaic inlays and some molten monochrome vases loses importance and disappears.

Achemenide glass production from the 5th-4th centuries BC (Western Persia) draw on the Assiran tradition of refined production, made with the lost wax method and commissioned from the formal metallic repertoire used as drinking vessels.

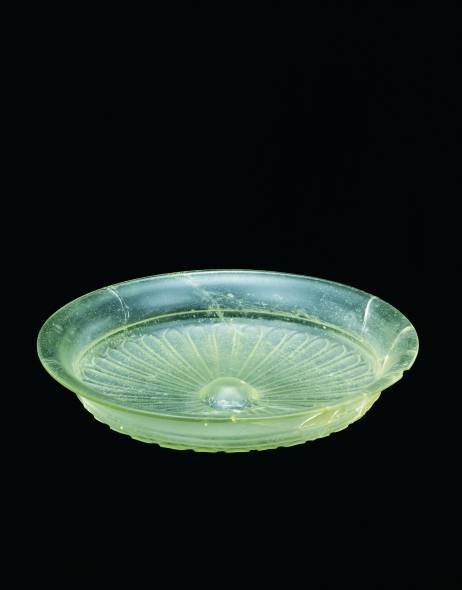

What we see are elegant shapes, in transparent monochrome glass, usually colourless, with yellowish or greenish glints, decorated with grooves or elaborate flower decorations outlined by carvings, positioned radially on the inside base (tab. I). They are mainly drinking vases inspired by precious metal vases: simple or lobed cups, phialai, phialai mesomphaloi (with central bulge) (photo 5) and lobed glasses (photos 6-7).

The production area is generally located in western Persia, but the spread of these products involves the Mediterranean basin, as seen in the discoveries from Derveni (Macedonia), Vani (Rhodes) and even touches Lybia (Aslaia), Campania (Cuma) and Emilia Romagna (Ferrara) (photo 8).

Their distribution coincides with the Greek and Macedonian trade routes and the identification of production areas along the Syriac coast or in the Aegean is difficult.

In the 5th-4th century BC, glass, despite its wide diffusion, is still considered a status symbol, as seen in Aristophanes in Acarnesi from 425 BC (Acharn, 72-74) which accompanies ... gold and glass cups ...

The West too in the 1st millennium BC is witness to some vitreous production, tied to production from previous centuries or derived from the import of new technologies from the near east.

Monochrome or decorated pearls continue to be produced and there are numerous examples. The Etruscan culture, for example, has given us a large number of them, used to make necklaces (photo 9) and bracelets or used to embellish fibula (photos 10-11) or fabrics. They are generally used for women and children, and for some scholars they must also have had a magical-protective value.

Amongst the decorated pearls, the one that stands out is the one called the 'eye' pearl. The oldest (9th-7th cent. BC), called 'easy eye' has large eyes outlined by white or gold thread (photo 12); the most recent ones (6th-4th cent. BC) are 'layered eyes', with the iris framed by various layers of glass (photos 13-14). The insistence of representing the eye, which has a protective value, are interpreted as amulets.

From the 7th century BC, the characteristics are long, cylindrical pearls, made of dark glass (brown, blue or green) with rod shaping, decorated with threads of coloured glass, found in Greece and Italy.

Mention should also be made of the big spherical pearls placed on bronze pins (photos 15-16) and the 'leech' coverings on bronze fibulas (photos 17-18), again with a decoration consisting of zig-zag or wavy lines. Some bracelets also have similar decorations (photo 18).

Materials found in the context of safe excavations, belong to Etruscan or Italic graves dated 8th-7th centuries BC.

The Etruscan area of central Italy and Campania, has given us about a hundred jars in blue or brown-amber monochrome glass, shaped on friabile core or on a rod, characterised by applied or pinched bulges (photo 20), which do not have any comparisons in the context of contemporary production of vitreous dishes in the Mediterranean basin. The shapes are always closed: oinochoai (jugs with a tri-lobed edged handle and mouth), alabastra, pyx and pear-shaped aryballoi.

They date back from the middle of the 7th to the middle of the 6th centuries BC.

The contents of funeral trousseaus in which they were found, generally reveal a strong presence of prestigious and exotic objects made of precious materials, thereby identifying the owners as members of the highest aristocracy.

Pinched-decorating is also found in some pearls that make up fibulas, widespread in Slovenia, Croatia and in Este, which are considered, on the basis of comparisons with Etruscan jars, from the same period.

A characteristic of the production from the Alp-Adriatic area is that of the so-called Halstatte-Tassen, cups of small dimensions, smooth or ribbed, sometimes with a handle, generally in yellowish, green-brown or transparent monochrome glass, most of which are decorated with scallops, discovered in Slovenia (Santa Maria in Tolmino and in the burial mound of Crnolica in Rifnik), in Austria (Halstatt)and in Trieste, dated the end of the 6th and over the 5th centuries BC.

Technically speaking, these high-Adriatic specimens were made using a die, with manual finishing.

There has been sporadic documentation amongst the Etruscans of the production of glass bracelets; it is with the Celtic culture (middle 3rd-1st centuries BC) that these become some of the most esteemed jewellery amongst women. Worn normally on the forearm, they are made of multicolour glass. They have decorations obtained with the use of glass of the same colour (photo 21) or with differently coloured threads (photo 22).

Two productions which were very widespread in the Mediterranean context were the so-called 'Mediterranean' jars and shaped pendants.

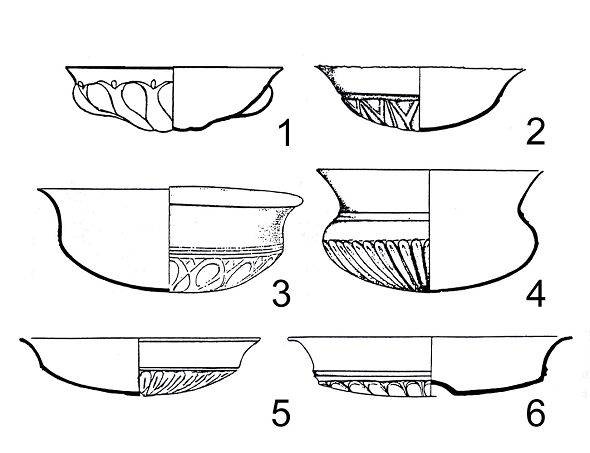

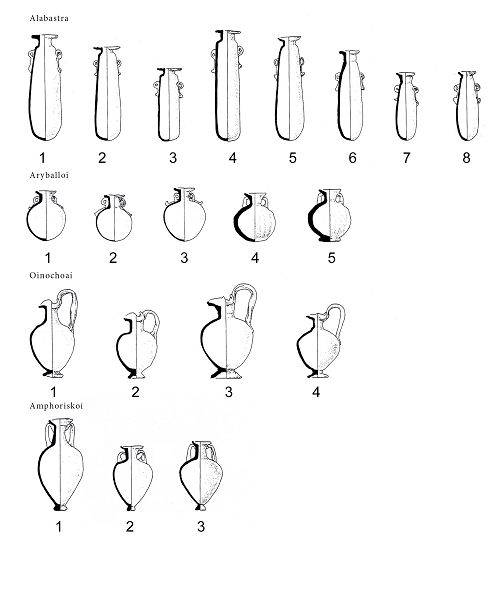

The 'Mediterranean' vases, which were mainly used to hold oils, ointments and cosmetics, have shapes which often look like Greek vases. Shaped on friable core, they generally date back between the 6th cent. BC and the beginning of the 1st cent. A.D. and are divided, on a chronological basis, into three groups.

Each period is characterised by a new repertoire of shapes, handles, decorations and colour combinations. The lack of archaeological discoveries related to glass industries does not allow us to resolve the problem of the identification of the production centre or centres and all the proposed hypotheses - albeit in the context of a common tradition - make reference above all to the high percentage of discoveries in some areas and to the vase shape they resemble.

The biggest and most homogeneous of the three groups is the so-called Mediterranean Group 1, dated back to the middle of the 6th to the beginning/first half of the 4th cent. BC.

The jars, whose shape looks particularly like the Greek vases like the alabastron, amphoriskos, aryballos and oinochoe, are mainly produced in dark glass (normally blue, less frequently in reddish-brown) with light coloured decorations (yellow, white and turquoise) (photo 23) or in light (white) glass with dark decorations (marc)(photo 24) made up of spiral or zig-zag lines, or feathered bands (photo 25).

In regards to the origin of this group, the most probable hypothesis is that this industry was developed in particular on the island of Rhodes following the movement of craftsmen from the near-east because their production is placed in the split of a glass tradition whose origins definitely go back to this area.

The statement of the widespread diffusion of these types in the Greek and Aegean world and the presence of the Greek element in the Syric-Palestine world, starting from the end of the 6th cent. BC (photo 26), seem to confirm that these glass products should be assigned to a 'Greek-Oriental' production, rather than a 'Phoenician' one, as has often been believed. In this regard, it is of note mentioning that the discoveries are documented in areas of the Mediterranean and the Black Sea where the Greeks traded, and that the trousseaus belonging to prominent people, reveal, in the majority of cases, the presence of Greek ceramics, in particular Attic.

Towards the end of the 5th - beginning of the 4th cent. BC, there is a disappearance of jars from the Mediterranean 1 group. The reason for this interruption is not known, but there could have been several causes: probably one of the reasons must be assigned to the decay of the three main cities on the island of Rhodes (Camiro, Ialisos and Lindos) at the end of the 5th century BC.

Another class of material which had widespread diffusion in the Mediterranean basin in that of shaped pendants, finished by rod shaping.

The identified pendants are: demonic masks (photo 27), small male heads with the features of a Negroid face, small male heads with straight hair and beard, sometimes with a turban, small male heads with long curly hair and straight beard or vertical splits, male heads with curly hair and beard (photo 28), small female heads with curly hair or with a turban-like band (photo 29), zoomorphic pendants (dove, dog, cock and ram's head) and other different ones (pearls with faces, bunches of grapes, bells, phalluses). What is particularly striking is the variety of the products and the use of polychrome to enliven and render the iconography more expressive.

The chronological periods of the pendants and the production areas, highlighted again by the concentration of discoveries and not by the sure testimony of the furnaces, are different according to the types. Even if the dating of the various groups could undergo some changes with the continuation of research, we can note that the oldest pendants, dated from the 8th to the 7th cent. BC, must have been produced in Egypt; the specimens from the 7th-5th cent. BC in Phoenicia and Cyprus with the possibility of drawing from styles in Carthage; while for the group dated from the mid-4th to 2nd cent. BC the Carthage role seems to be the predominant one; in the Hellenistic era, we also see production situated in Rhodes, Cyprus and Egypt. The data collected concur in the recognition in this vitreous production of the original contribution of the Phoenicians.