Description

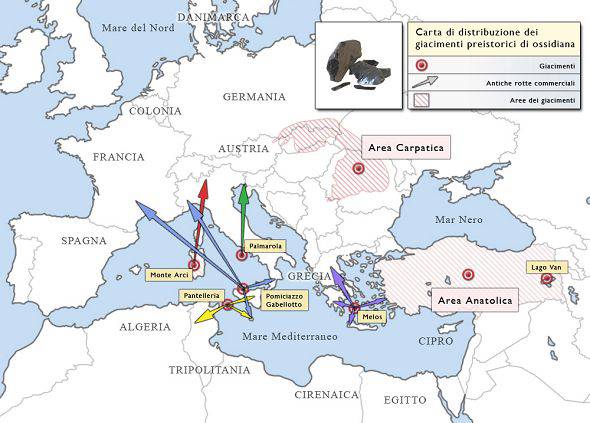

From the 6th millennium BC, man begins to use obsidian (photo 1), a siliceous rock of volcanic origin, found in abundance on the Eolie islands, Pontine, Pantelleria e Sardinia (Monte Arci) to make sharp and resistant objects. This material is traded over long distances, giving rise to the first Mediterranean trade routes (map A).

The discovery of the actual vitreous material, in the form of faïence (photo 2) or a glassy paste, dates back to the middle of the 3rd millennium BC in Mesopotamia (Iraq and Syria), and is preceded only by the use of glazing. Semi-finished glass, in the shape of a bar or block, dating back to the 23rd century BC, was discovered in Eshnunna and, back a few centuries, in Eridu.

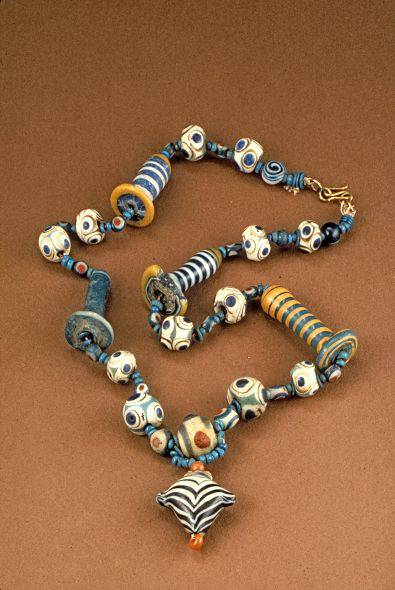

The first shaped and moulded glass objects were necessarily very small. From the appearance of the first containers, apart from buttons, almost only ornamental or ritual-type objects are produced, in particular pearls of various dimensions, small plates and inlay work (photo 3).

This production reaches the eastern Mediterranean and the European coasts as testimony to a series of trans-ocean relationships between the communities at the beginning of the Bronze Age and the Aegean environment. The oldest occurrence of pearls in a glassy material were found in French Languedoc between 2400 and 200 BC (hypogeum from Roaix). In Italy the oldest discovery dates back to the 19th-18th century BC and is a necklace from the Caverna dell'acqua in Finale Ligure. On the continent, following contacts with the Carpathian-Danubian regions, the Lago di Garda region gave us many discoveries of biconical pearls.

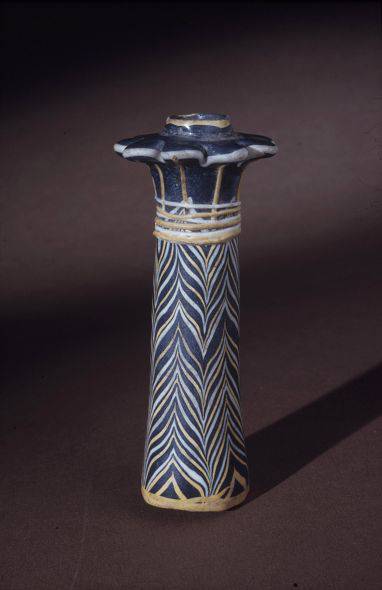

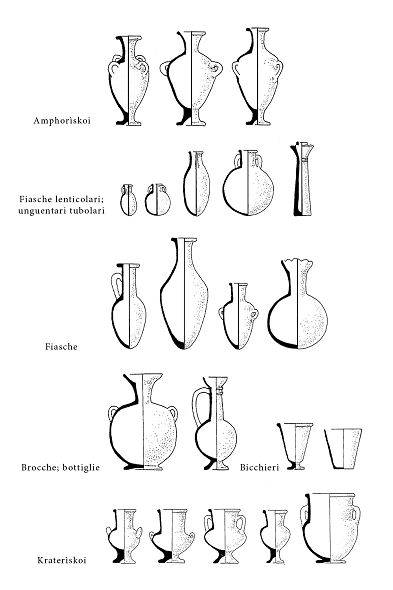

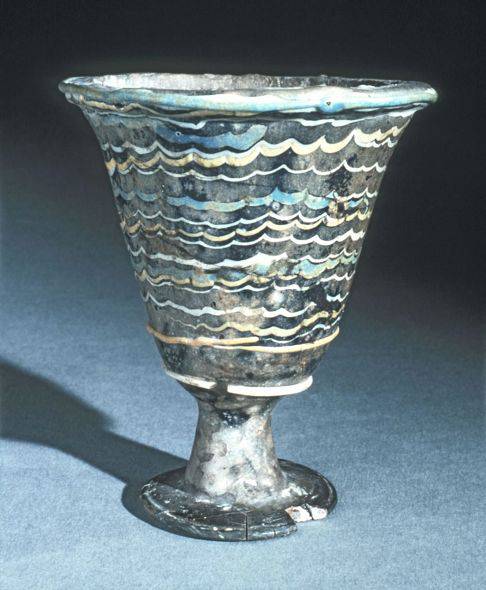

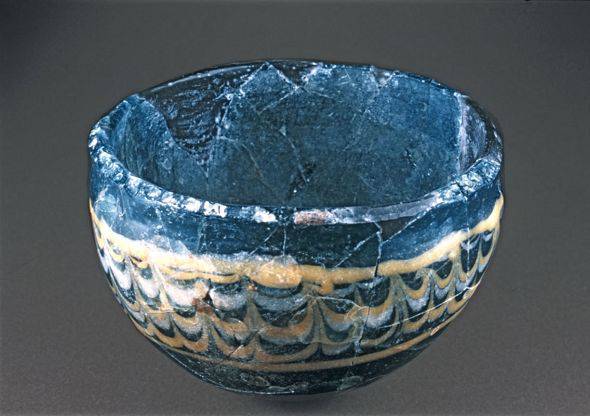

The first containers made of lass seem to have been produced over the 16th-11th centuries BC, initially in the ancient Alalakh (in the Antiochia plain, North Syria) and the High Mesopotamia, in Nuzi, Assur, Tell al-Rimah, that is to say, in the Hurritan-Mitannic area. They are small ceramic objects, shaped like chalices, cups, small pear-shaped bottles tapered downprevalently in blue glass, decorated with different coloured filaments, especially yellow.

Technically speaking, these objects were made by fusion on friable core which conditioned the size of the object.

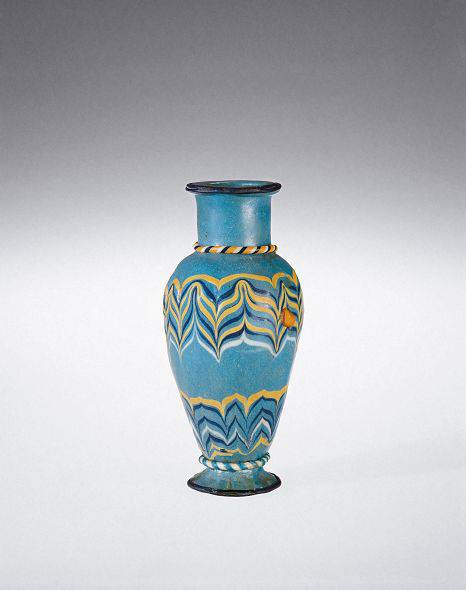

About a century later, glass production developed in Egypt too, with an ever-increasing independent style, probably as a consequence of the military successes of Thutmosis III (1479-1425 BC) in Mesopotamia. Egyptian production is characterised mainly by cosmetics containers (photo 4), ritual vase (photo 5) and shaped vases of bright polychrome.

Shortly after the introduction of the friable core technique, over 15th-14th century BC, production of polychrome mosaic vases were experimented, again from the northern Mesopotamia area, which will be the site of wide successive developments.

At the same time, mosaic glass is discovered also in Egypt, as the numerous fragments found in Malkata testify, which probably belong to the Amenofi III reign (1390-1352 BC). From this moment on, Egyptian glass production experiences a period of notable splendour for the variety of shapes and the chromatic wealth (Table I - photos 7-8-9-10).

The spread of Egyptian products reached Mycenaean Greece, while in Cyprus, the production of pomegranate containers began (photo 11).

In Mycenaean Greece, lace elements were almost exclusively the only thing made (photo 12), blue in colour, shiny and translucent and decorative plaques for the inlay of palatial furnishings. These were secondary, as seems to be demonstrated by the findings of ingots at the Ulu Burum relict, on the southern coast of Turkey, belonging to a boat from the 14th century BC, probably directed towards the Hellenic peninsular.

In the western Mediterranean, along the Tyrrhenian and Adriatic coasts open to Aegean traffic, in the initial phase of the Middle Bronze period (c. 15th cent. BC), there are globe-shaped and disc-shaped pearls in molten glass, which can be compared to similar Mycenaean materials. These ornamental objects, a sort of status symbol, are found in houses and coeval funerary contexts in centre-south Italy, like the Punta d'Alaca settlement on the island of Vivara (Naples), and Grotta Manaccora in Puglia, in Sicily (Castelluccio, Fogliuta di Adrano, Monte Grande, Thapsos) and the Eolie Islands (Acropoli di Lipari, Capo Graziano).

In the middle Bronze era, vitreous material even reaches the Padana plains: we know of particular conical and disc-shaped buttons like the examples from Poviglio and Quingento in the Parma area and the pilework in Mercurago (Novara).

Around 1200 BC, coinciding with the events which would determine the end of the Bronze Age, there is a reduction of the production of vitreous objects (photo 13), as a consequence of the decline of the Mycenaean civilisation of southern Greece, Crete and the Ittita reign in centre-eastern Anatolia, which determined the flowering of luxury goods' production and the conditions for their commercialisation.

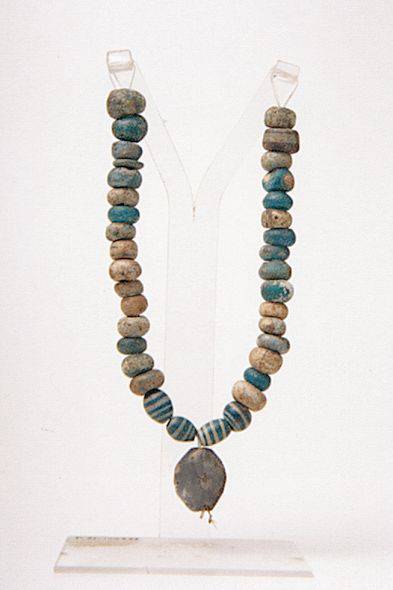

In the decline of Egyptian production, there are few archaeological sites that, between 1200 and 900 BC, have given us vitreous discoveries: they are mainly necklace pendants and small sconces.

Lastly, in the late European Bronze era (6th-9th cent. BC), local production (photos 14-15) is activated in the north-east of Italy, in Frattesina di Fratta Polesine (Rovigo).

We are talking about various types of pearls (photo 16) in bright colours, in blue sky-blue and red, presumably obtained by coating or wrapping the molten glass around a rod, decorated with the addition of some molten glass threads (photo 17).

At the end of the 2nd millennium BC (11th cent. BC), a necklace of polychrome pearls in molten glass from Lipari (Piazza Monfalcone Necropolis) (photo 18) documents the continuation of the long glass 'ornamental' tradition which persists even in the changed political and economical situation of the Mediterranean, which has a negative effect on production.